TLDR: If you reduce your critical path size from 90 to 60 KB, it's good, but not all that great from a networking perspective. But going from 42 to 40 (especially on slow connections) might be more prominent. Always look at the cheat sheet and try to get to the smaller round trip size. I made those numbers bold so you can see if you are close to any of them.

Cheatsheet of round trip sizes (in KB):

| Round trip | Window Size (KB) | Total size (KB) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 14 |

| 2 | 28 | 42 |

| 3 | 56 | 98 |

| 4 | 112 | 210 |

| 5 | 224 | 434 |

I hope you don't need more for your critical path, but if you do, don't worry about round trips yet. Check the end of this article and some of my other articles for some tips.

Recently I read a couple of useful articles on how TCP works and

especially how it snowballs (or slow-starts) with small packages into

bigger chunks of data over the life of a connection. It is a little

known fact that if your webpage critical path (basically HTML + CSS) can

fit into the first round trip within a TCP connection, it is the

best-case scenario because the browser will not ask the server again for

anything.

This rarely happens as webpages often use CSS frameworks, inline

JavaScript, or have a lot of text on them. But there is also the

second-best thing. Return your webpage within two round trips or three.

The first round-trip has a size of 14 KB.

The second one is the double of that. Which is 28. So at the end of the

second round trip, your webpage will be loaded if it's below 28 + 14 =

42 KB

Again, the third round trip is double the previous one, which is 2 * 28 =

56. 56 + 42 = 98. For quick reference look at the cheat sheet at the

top of the article.

We adjusted the homepage of our documentation website to fit in the first round trip. It was around 18 KBs, but had a lot of inlined stuff, and was optimized pretty well (already had 100 in Lighthouse).

To go below 14 KB, we had to un-inline some things (mostly SVG images, favicon, which was another experiment in the making), clean up some unused SVG symbols (for icons), and at the end of the day, we landed at 12.17KB. 5.29KB for HTML and 6.88KB for CSS (thanks to TailwindCSS+PurgeCSS).

Well, it's hard to tell. SSL handshakes take more time than the

actual transfer of the critical data, so it is not bad from the frontend

point of view.

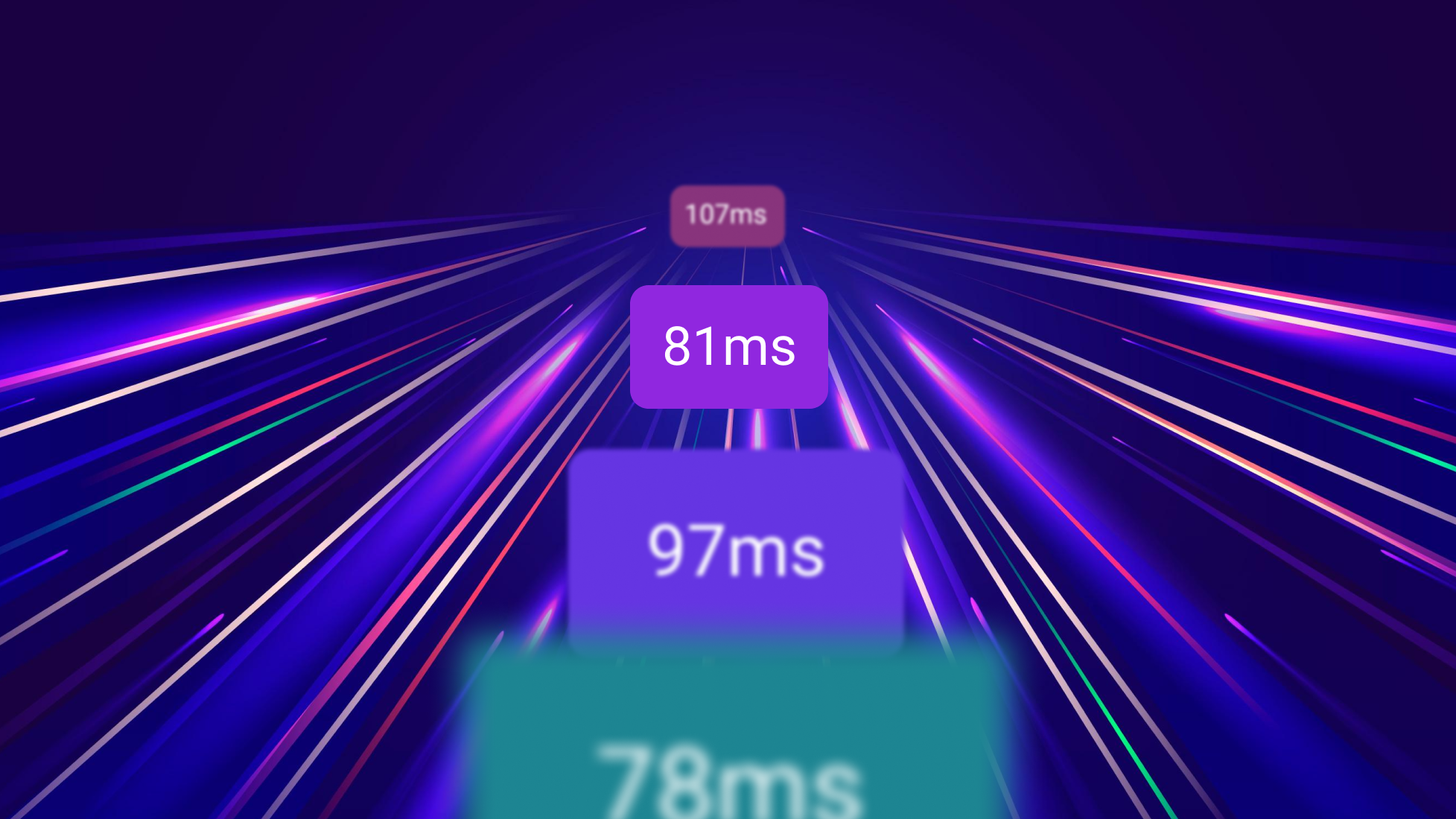

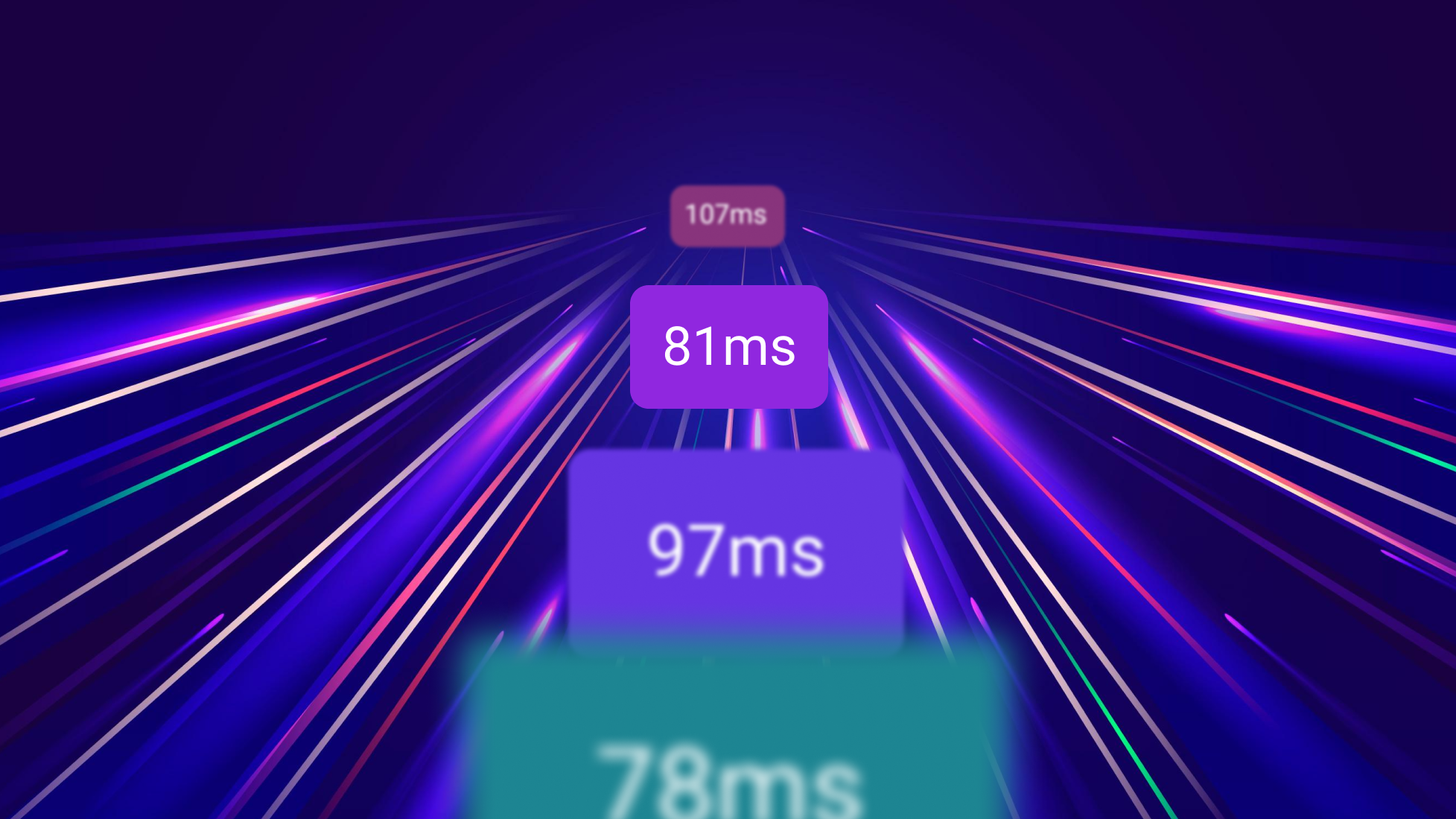

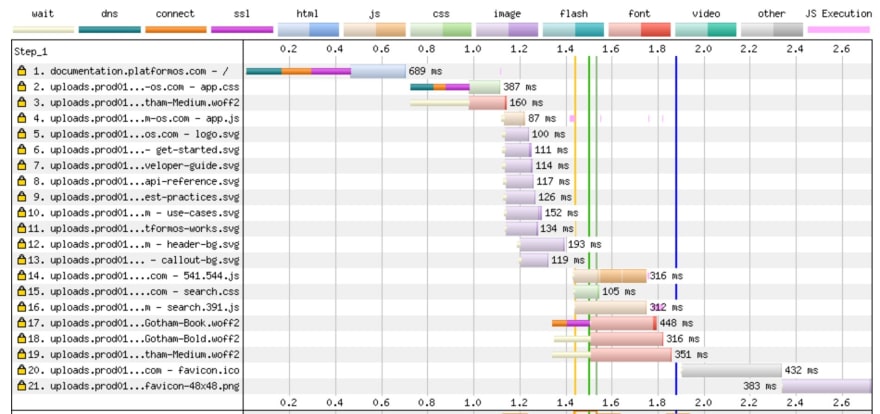

This is the waterfall before we managed to get below 14 KB:

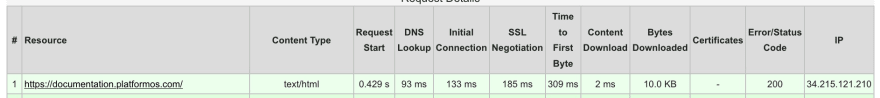

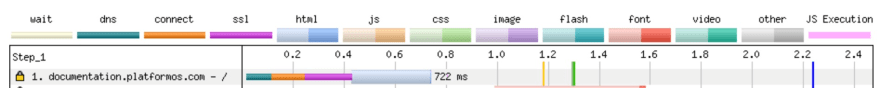

And this is after going below 14 KB: (+ addition of preconnect in HTTP header to hopefully speed up connection initialization to our CDN):

Note: Tests were made on the 1.5Mbps setting of WebPageTest.

After the tests, we discovered that SSL handshakes can be optimized, so this will be our target very soon to make global improvements. We detected that our SSL handshake data weighs around 6KB, and it might account for the 14 KB TCP packets. We need more investigation in that area because there might be more to gain.

The nature of testing on live websites with real devices is that you can't really predict exact numbers. Network conditions on both sides change. Device load matters. Many things can vary, and I could run the test a couple more times to prove my point, but I prefer to prove a different point: Just because something is better, it does not mean you will be able to show it on a chart every time. This is real life, not a laboratory.

Just for the sake of testing, I inlined the main CSS on the homepage to see what kind of results this will give. In the critical path it removed one SSL handshake, so in theory, it should move everything left on the waterfall chart.

I did it by populating the Liquid partial with CSS after assets are built. A couple of lines of JavaScript did the trick:

const { writeFileSync, readFileSync } = require('fs');

const css = readFileSync('../app/assets/app.css').toString();

const fileContent = css.replace('./fonts/Gotham', '/assets/fonts/Gotham');

writeFileSync('../app/views/partials/layouts/head/inline-css.liquid', fileContent);

Results with inlining:

It did very well - HTML and CSS were loaded just after 722ms, within one round trip within the first request. For the time being, we are not going to use this technique in production because of the added complexity in the development process. One day we will find a better way of automating this process, and it will become a reality.

Answering the question from the title: Should you always care about your website size?

Yes. It's always better to have a smaller website than a bigger one. Even if you cannot get spectacular results today, remember that good results come from a lot of smaller changes. So go for it, one step at a time.

And no. If you are reducing 100KB from your 2MB React app, don't stress about it. There are more effective ways of spending your time, for example:

All of those have proven to be very effective in improving user experience while being relatively fast to implement — one step at a time.

Ensure your project’s success with the power of platformOS.